Good Laboratory Practice standards were first discussed in the 1970s when the realization came to light that you can't always take scientific data at face value. Before that time, the assumption was that the study was always done properly and recorded precisely. Pretty naive when you think about it. That's not to say that any action outside of GLP standards is malicious, all too often it's done out of ignorance, which is why it's so important to have well qualified and fully trained people who understand the importance of GLP.

People who don't understand the importance may balk at GLP because it is detailed, it is rigid and there is very little wiggle room. What does the minutiae matter? Isn't it just the final outcome that matters? Why the obsession with the process?

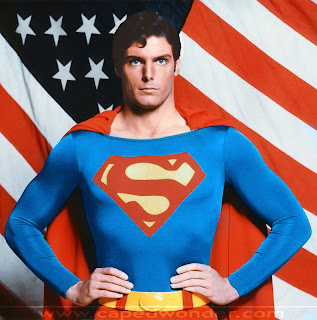

Killing Superman: A Parable on Good Laboratory Practice

One day in Gotham an analyst at Gotham Laboratories Inc was preparing her Hal 9000 to analyze water samples for Kryptonite levels. Lex Luther was at it again and there were a group of wide eyed orphans clutching teddy bears, stranded on an island surrounded by rising water. It was a sad sight, and Superman was chomping at the bit to go rescue the tiny tots.

There was just one problem. The water surrounding the area was not only fast moving and too dangerous for the mere mortals to rescue the orphans, but it was known to often be contaminated with Kryptonite. It was too dangerous for Superman to plunge in, he needed the laboratory tests first.

The Hal 9000 was calibrated, but when the analyst looked at her low Kryptonite control she could just barely see it. This wasn't good. The standard was at 5ppb. Although a low environmental level, it was the highest level of Kryptonite Superman could function with. Recovery was supposed to be at least 80% so that they could be sure if there was Kryptonite there, they would see it and thus be able to warn Superman. Not seeing the control was just not going to cut it.

The Hal 9000 was calibrated, but when the analyst looked at her low Kryptonite control she could just barely see it. This wasn't good. The standard was at 5ppb. Although a low environmental level, it was the highest level of Kryptonite Superman could function with. Recovery was supposed to be at least 80% so that they could be sure if there was Kryptonite there, they would see it and thus be able to warn Superman. Not seeing the control was just not going to cut it.Perhaps the standard was old? So the analyst opened a new bottle and ran it again. Nope, no good. Perhaps the calibration standards needed to be re-prepped? So the analyst re-prepped the standards. Nope, still couldn't see the low Kryptonite standard properly.

The analyst had worked at Gotham Laboratories Inc. for a long time so she knew the Standard Operating Procedure and she had done the first two steps for correcting a low control. The next two instructions in the SOP were to troubleshoot the instrument as needed, and then if that didn't work to contact the manufacturer. No problem, troubleshoot as needed. The instructions weren't anymore direct than that because, well... how do you document every possible thing that could go wrong and it's fix? I mean, that's why you have highly trained individuals in those positions.

But alas, Gotham hadn't quite embraced the GLP standards yet and where in another laboratory only the senior level analysts would do the troubleshooting, that wasn't a consideration here. I mean, that's what the checks were for on the instrument. If they didn't pass then you knew it wasn't working right and if it did, then it was. The outcome was simple.

The analyst knew there were things she could probably do like changing the lines or cleaning the cones or giving the Hal 9000 a good pep talk but the water was rising, her boss was being a jerk, the finals of American Idol were on TV and well, the way the Hal 9000 kept calling her "Dave" was creeping her out.

The control just wasn't visible so the answer was simple. She'd just add more. So taking her same low level Kryptonite standard she simply doubled the amount of her aliquot. Restarting her run and ignoring the question of "What are you doing Dave?" she watched for the control's results. It was beautiful! 90% recovery. Now all she had to do was run the water samples, Superman could save the orphans and she could go home.

I mean, after all, she fixed it right? The control passed. Well, not exactly. She did indeed get her run to pass, but she didn't fix the problem. Whatever was making the Hal 9000 unable to see the low level of Kryptonite was still there but the run passed. Now of course the problem was that the point of the test was not to get the control to pass. The point of the test was to get accurate and reliable results in those unknown water samples. Running the control was just a way to be sure the instrument was working properly.

Those water samples that had been taken so carefully across the gradient of water Superman would have to pass were analyzed and things looked good. They were all below the low level control. Superman would be safe! Hurray!

Her boss was happy, the people of Gotham were happy and Superman went into the dangerous passage to get those poor orphans off that cursed island. Now the roof above the treacherous water was spiked and dangerous so Superman would have to swim, but he knew he could do it safely because the run passed and the Hal 9000 didn't see any Kryptonite in the water.

As Superman swum, he started feeling a little ill and half way there he went under. The crowd was stunned! What could do this to Superman? Only Kryptonite surely and they had tested for that. The run had passed!

Oh, but alas, double spiking the standard hadn't fixed the instrument, it only masked the problem and while it wasn't written anywhere that she couldn't do that; if the analyst had been familiar with GLP she would have known that changing the procedure to make a test pass was wrong and that forcing QC to pass can lead to erroneous results.

But alas, Gotham had no GLP and Superman was dead. Those poor orphans.

And thus the importance of Good Laboratory Practice; because the point is not to get the controls to pass, the point is to get accurate results on those unknown samples.